Marcela Guerrero Medina

Art History Department

University of Wisconsin-Madison

mcguerrero@wisc.edu

“The steps of the tango form a kinetic memory of the candombe,

a dance that has died but in dying gave birth to the dance that

identifies Buenos Aires, a dance exported around the world.”

George Reid Andrews

“E e e bariló,” “E e e mbadi lo”(1)

or “bring out the drummers,” was a popular phrase hollered at midnight

by Afro-Argentine attendants at the Shimmy Club in Buenos Aires,

Argentina. At late hours of the night, in the basement of the Swiss

House and underneath the main floor where conventional dances such as

jazz, waltz, and tango would play, the black aristocracy of the capital

would congregate to dance to the beat of candombe—a term of Kimbundu and Ki-Kongo origin and which in Argentina came to mean “the music and dance of blacks.”(2)

As the night started to come to life, prominent families from the black

community in Buenos Aires would sit in tables surrounding the dance

floor. Reminiscent of an Archibald Motley painting depicting the urban

flavors of a Chicagoan club, anyone that wanted to dance at the Shimmy

Club would step into the circle to let the atmosphere of laughter and

light conversation embrace him or her. The camaraderie went on until

midnight, when suddenly black Argentines on the floor would shout

“¡afuera los chongos!” (chongos get out!) referring to the white folks

dancing among them. “E e e bariló,” “E e e bariló,” and Afro-Argentine

drummers would take the stage while the black elders would take the

dance floor.(3)

The Shimmy Club, founded in the early 1920s and in business until the

70s, represents a microcosmic space where the beat of Afro-Argentine

culture remained alive and strong despite efforts at “Europeanizing”

Argentina. This paper will examine what I call the seeming “push and

pull” effect seen in Argentine culture; as the country’s European

veneer became more visible, the African influence decreased to the

extent of almost invisibility. This process is neatly retained in the

politics of tango. As long as its African sources were noticeable,

tango dance and music did not occupy the rank of national icon;

however, tango’s approval came after it was masked with European

traits, aiding to proliferate at the same time a larger national and

political project of turning Argentina into the “Europe of the

Americas.” As Charles Chasteen mentioned in his essay “Black Kings,

Blackface Carnival, and Nineteenth-Century Origins of Tango,” in the

1900s tango had been “bleached and ironed during its stay in Paris,

replacing its funkiness and hunched shoulders with languid glides and

pointy toes.”(4)

The zenith of the popular phrase “no hay negros en la Argentina” (there

are no blacks in Argentina) takes place at a moment in the history of

tango when black traits had been almost entirely whitened.

As the title of this paper indicates, the overarching aim will be to

step back figuratively so as to scrutinize the correlation between the

discursive and cultural erasure of Afro-Argentines and the growing

tendency of populating Argentina with Western-European people and

traits. To some people—Argentines included—the title of this essay

could sound oxymoronic since the terms “African” and “Tango” are seldom

found in the same sentence, let alone expressed. Only scholars

interested in Afro-Atlantic studies and some members of the

Afro-Argentine community have fought the theory that claims that blacks

have “disappeared” from Argentina.(5)

The crux of the problem appears to be an issue of “visibility” or the

lack thereof. Thus, one of my goals in this paper is to ascribe in

these pages the visibility of Afro-Argentines, especially in tango

music and dance. I wish to leave the reader with a sense that tango—as

both music and dance—is a kinesthetic and cultural experience that

transcends temporal and spatial boundaries, thus allowing us to recover

and re-cover tango with its African traits. As our hearts beat to the

rhythm of a drum used in candombe or a bandoneón

played during a tango song, we become kinesthetically implicated in

recovering the pounding pulse of Argentina’s Afro-foundation.

“Convert the outrage of the years into a music, a sound, and a symbol”(6)

is a famous verse by acclaimed Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges and

is exactly what Afro-Argentines did when they participated in the many

forms that prelude tango. After presenting a short yet essential

summary of the history of black people in Argentina, my second goal

will be to explain such dance-related terms as malambo, payada, candombe, milonga, and canyengue

in order to show how “visible” the African tradition was and what is

still retained. As time progressed, however, politicians found some of

these traditions detrimental to their project of “Europeanization.”

After being stripped of black traits and masked with a Parisian patina,

tango became the national icon that enjoyed international success.

Nevertheless, as part of tango’s globalization, other world dances—most

of which have an Afro-foundation—left an imprint that would connect

tango back to its African sources. It will be my third goal in this

essay to discuss tango in the international arena.

I. Rapping Back at History: Afro-Argentina Lives in Malambo and Payada

According to a letter written on the 26th of September by Jesuit priest

Ignacio Chome, in 1730 there were 20,000 men and women in Buenos Aires

who were black(7).

In his letter, the priest exclaimed surprise at learning the number of

black people in a city of 10,000 white inhabitants. Other epistles

reveal that some enslaved people were also smuggled into Buenos Aires

via Brazil. In any case, priest Chome mentioned that 90% of the blacks

in Argentina came from Angola and the language that was mostly spoken

was Kimbundu. Forward almost 50 years later; the number of people of

African descent could go from 25% to more than 50% depending on the

region. In 1810, the Afro-Argentine population in Buenos Aires reached

a peak of 30%. The census of 1887 questionably reveals that only 2% of

the Argentine population was black(8).

One must be doubtful, however, of these numbers since by the late

nineteenth century there was already a project established of

physically and symbolically changing the visage of Argentine identity.

Scholars such as George Reid Andrews and Alejandro Solomianski go a

step further by questioning the truthfulness of the census of the last

part of the nineteenth century. For them, the drop in the

Afro-Argentine population could have been accelerated artificially

through official tallies(9).

Nevertheless, it remains true that throughout the nineteenth century

there was a considerable decline among the black population due to a

combination of historical events.

The

Afro-Argentine community’s lack of physical visibility must be founded

on veridical—even though deplorable—information. This is not the case

of the myth

of the purported total “disappearance” which helped exacerbate the drop

in numbers of black people in Argentina. The historical events that

must be acknowledged, however, were the several wars in which the

country was involved during this century. Starting with the Argentine

War of Independence in 1810 and other subsequent wars, many

Afro-Argentines fought and died for their country. Even after the Ley de la Libertad de Vientres (or Freedom of Wombs Law), which declared free any children born from enslaved women after January 31, 1813(10),

many black men were “volunteered” by their masters to go to war. The

time spent fighting for their country, and in an oblique way for their

freedom, represented a period of increased miscegenation. Clearly, the

wars served to hasten the genetic whitening of the Argentine population

by keeping black males from having progeny with black females(11).

Moreover, a cholera outbreak in 1868 and yellow fever epidemics in 1871

and 1873 further reduced the black population. The total death toll was

over 20,000 and the percentage of black people who died in all

probability was extremely high. This seems to be a logical conclusion

since the two neighborhoods of the city hardest hit by the epidemic

were La Boca and San Telmo, the areas of greater concentration of Afro-Argentines(12).

Partly as a way to substitute the large number of deceased, the massive

immigration of Europeans came to represent cheap labor in urban and

rural settings. Thus, as journalist Narciso Binayán Carmona candidly

puts it, white immigration has categorically divided the history of

black Argentines into a before and after(13).

Even though it fits outside the scope of this paper, it is worth asking

whether the decline in numbers of black people who fought in the wars

or died from cholera or yellow fever was part of a larger policy of

demographic racial cleansing carried out by caudillos or

commanders who, moved by the liberal spirit and yearning of breaking

free from Spanish rule, sought to create a creolized Argentine identity

that was up to par with its Spanish counterpart? Furthermore, even if

the numbers waned, Afro-Argentine identity was still carried by those

who survived the wars and the diseases and by the multiple generations

of mixed descendants that are very much visible even today. Even if the

presence of Afro-Argentines did not appeal to the sight of members from

the elite circles, black dances and their music were indeed felt by

white Argentines.

The centralization of Buenos

Aires in Argentine’s politics and culture tends to elide discussions of

the interior regions of the country. In the pampas—the

plains widely known for occupying a large section of the Argentinean

countryside—many black workers were initially brought as slaves. Next

to the gauchos (Argentina’s beloved cowboys) blacks developed the malambo

dance. According to Robert Farris Thompson, it has a modicum of Central

African influence which is perhaps most visible in the dance’s clear

Kongo name(14). In malambo

the upper half of the body maintains a rigidity that is Andalusian in

nature yet the footwork is meant to be complex and sophisticated so as

to challenge and eventually win over an opponent. The exchange of dance

steps is reminiscent of the “call-and-response” structure of Central

African song and dance(15). Malambo’s feistiness is doubled once the payada comes into play. Payada puts guitarists face to face with each other in a duel of strumming and verse(16). Just like the body of a malambo dancer, the influences in payada are split in half: on the one hand, payada

is the lineal descendant of the African tradition of musical contest of

skill but it also comes from the challenge songs found in the Iberian Peninsula(17). As in rap, the one who “spits” better wins.

As a matter of fact, one of the best payadores was the Afro-Argentine Gabino Ezeiza(18). Ezeiza, natural from Buenos Aires, represents the tradition of payada in an urban setting. In true battle form, Ezeiza rhymed sophisticated insults and rapped them to his opponents.

I see no equality

In this here rink:

I improvise, simply and quickly,

You have to sit down and think(19).

As stated already, even though the dance and music of malambo and payada started in the rural regions of Argentina they were quickly brought to the city where, combined with the tradition of candombe, contributed to the visibility of Afro-Argentine’s cultural expressions.

II. A Political Hot Potato: Blacks, Candombes, and Retaining Culture In Spite Of

Some years before gauchesque musical traditions reached Buenos Aires, the practice of candombe

had already been established since the 1830s as an Afro-Argentine

tradition. The term is a combination of Kimbundu (ka = ‘costume’) and

Ki-Kongo (ndombe = ‘black’)(20) but in Argentina, the word candombe

came to represent a dance, a music, and a place of congregation. It did

not lose, however, the notion of ethnic pride, implicit in the original

African word.

According to Alejandro Frigerio, a scholar who has

studied the cultural traditions of black people in the Southern Cone, “candombe

is played in private meetings in houses, but also surfaces many days of

the year in small (callings), group gatherings parading through their

neighborhood playing the drums.”(21) Candombe achieved great visibility during carnival, especially around the neighborhood of Palermo. Contemporary llamadas

take place in another historic zone, in San Telmo, which by the

mid-nineteenth century was known as “el Barrio del Tambor” (the

neighborhood of the drum) since several African nations resided here.(22)

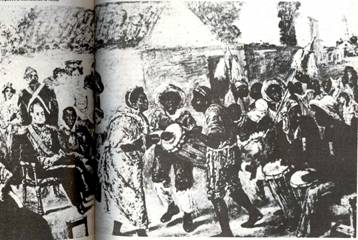

Pedro Figari’s paintings give us an insight into the choreography of candombe

(fig. 1 and 2). Traditionally men and women stand in opposite rows;

this was called the courtship. Standing in front of your partner but

without touching each other, couples would move their bodies forward

and back while shrugging and advancing the shoulders a bit and sticking

the buttocks out(23). This was the prelude to the ombligada or striking of the bellies. Robert Farris Thompson explains that this movement, also called bumbakana, is the climax of Kongo dancing(24).

This brief invasion of your partner’s space is an acknowledgment (one

might also call it teasing) of the importance of procreation in life.

Even though candombe eventually morphed into a new version,

probably influenced by other dances, it remains true that for most of

the nineteenth century this tradition represented a direct reflection

of a conflation of Central African dances. With the movements of candombe,

Afro-Argentines directly challenged the elite’s whims of not “seeing”

black traits in their culture. White Argentines in the upper circles

perhaps did not “see” black people but they surely “felt” black dances.

Fig. 1. Front cover of Todo es Historia, published in November 1980. Published with permission of Todo es Historia.

Fig. 2. Pedro Figari, Candombe Federal, n/d. Oil on cardboard, 24.4" x 32.3". Published with permission of Fernando Saavedra Faget.

One Argentine president who did embrace the tradition of candombe

among black Argentines was Juan Manuel de Rosas, who governed Argentina

from 1829-32 and then from 1835-1852, and was renowned for being a

populist. His policies indicated a defense of Argentine nationality and

creole values. A member of the Federalist Party, Rosas was famous for

attending—along with his daughter Manuelita—candombes

organized by different African nations in Buenos Aires (fig. 3). While

Rosas was obtaining the support of the black population (undoubtedly as

a political strategy), as well as that of other sectors of Argentina’s

underbelly, he was also making enemies among the upper crust of

society. The Unitarians, Rosas’s adversarial party, wanted a

centralized government in Buenos Aires and wanted Argentina to get rid

of any “uncivilized” traits, a euphemism used at the time to denote

Indians, gauchos, and blacks. In turn, Rosas made sure the

Unitarians did not affect his administration by exiling and terrorizing

its members. Later, when the Unitarians gained control of the

government, they embarked on a large-scale project of retaliation

against supporters of Rosas’s governments—including, of course, black

Argentines.

Fig. 3. Candombe in the presence of President Juan Manuel de Rosas. Published with permission of Todo es historia.

It is believed that in 1865 when the Paraguayan War began,

President Domingo Faustino Sarmiento used black and gaucho troops as

cannon fodder(25).

Sarmientos’s figure is important in the discussion of the purported

“disappearance” of black Argentines because his crusade consisted of a

scheme that sought to obliterate their presence at a physical,

discursive, cultural, pedagogical and clinical level. Led by the mottos

“Europe in America” and “to govern is to populate,” president Sarmiento

advocated strong immigration policies that gave Argentina, what

professor Marvin A. Lewis calls, a “massive blood transfusion.”(26)

Continuing with this clinical trope, it is known that Sarmiento

prescribed a type of immigration that would “correct the indigenous

blood with new ideas ending the medievalism”(27)

in which the country was caught up. It is evident that in referencing

Louis Agassiz in one of his books, Sarmiento thought that the concept

of racial mixing was unthinkable in his project of advancing Argentina

into a more European-recognizable nation.(28) The Ley de Avellaneda (Avellaneda’s Law), passed in 1876, gave the green light for thousands of immigrants to enter Argentina(29);

if the number of Afro-Argentines was in decline, as the government had

been wanting us to believe, the hordes of Europeans would decisively

finish overwhelming the black population and their contributions to the

arts in Argentina—or would it?

Furthermore, the fact that Sarmiento is seen as the father of

Argentina’s educational system cannot be overlooked. Thus it is quite

plausible to consider that, by having the structuralization of the

public school system under his control, it was probably very easy for

Sarmiento to indoctrinate in young white Argentines and recently

arrived immigrants the discursive rhetoric of the disappearance of

blacks in Argentina. A revision of these political devices that sought

to eradicate Afro-Argentine’s presence serves to set up the context in

which the blacks’ artistic contributions survived despite the

unfavorable circumstances.

III. Two Resilient Dances and a Prelude to Tango: Milonga and Canyengue

If there has ever been doubt about the presence of African descendants

in Argentina, it only suffices to consider carefully the term milonga. As a cultural African descendant, milonga

is an upbeat, faster, let-your-hair-lose kind of dance made popular in

the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. The term is derived

from Kimbundu and classic Ki-Kongo words meaning “argument” and “moving

lines of dancers,” respectively(30). As a dance and as a type of music, milonga is the urban counterpart of malambo and payada. Robert Farris Thompson goes even further by saying that “when payada reached Buenos Aires, the city renamed it milonga.(31)” From payada, milonga still retains competitive and argumentative qualities that make it such an interesting dance to watch. Milonga’s

high tempo can tempt any couple to bring it on into the dance floor and

show off their most creative steps in an attempt to challenge any brave

bystanders into a duel. Thus, even if milonga is not a

verbalized argument, it does represent a calling among couples to enter

into a kinetic quarrel for the purpose of determining who the best milonguero is.

The other African meaning to which the term milonga alludes—“moving lines of dancers”—calls to mind the first stage of candombe in which men and women form two lines facing each other, singing, chanting, and swaying to a slow and steady beat(32). Even though milonga

bears the Western trait of dancing in couples, often one can appreciate

that the “moving lines of dancers” have moved to the periphery by

forming a circle surrounding the performers. Two other African elements

that are worth noticing and that are subtly retained in milonga are the sudden pose struck when the end of a song is announced by uttering the words chan-chan and the offbeat pattern of the footwork(33). Thompson identifies this final gesture as having roots in the idiomatic Ki-Kongo expression tshia-tshia, meaning “step it down” or “perform(34).” However, as a crucial ending, chan-chan’s source comes from the dances among the Akan people in Ghana(35). The offbeat footwork came as a result of trying to make milonga similar in rhythm to candombe, hence the quick insertion of an additional step in between beats.

In very subtle ways, milonga

was able to hold on to some characteristics that had been passed on

down the lineage of black Argentine dancers and musicians.

Nevertheless, it is worth pondering on the reasons behind the slow

dwindling of African and Afro-Argentine traits and the steady increase

in the Europeanization of milonga. An article titled “The

People of Color” from 1905 throws light on this issue. The author, Juan

José Soiza Reilly, congratulated blacks on changing their style of

dancing. Soiza Reilly described how “instead of the grotesque candombe

or s[a]mba—lewd as a monkey’s grimace—they dance in modern clothes in

the manner of Louis XV.(36)”

This quote is important because it demonstrate two things: first,

Afro-Argentines at the turn of the century were negotiating their

traditions via mimetic representations of white’s codes of behavior

(i.e., what to wear, how to stand, what gestures to make) while also

maintaining traits that, in the long run, could be linked back to an

African heritage and to an Afro-foundation. However, the theatrical

revue Homburgs and High Hats announced the end of milonga in 1906(37),

a year after Soiza Reilly had congratulated Afro-Argentines at finally

succeeding in assimilating the forms of white Argentines. The closeness

in time between these two announcements leaves one wondering if milonga’s demise in 1906 came as a result of the acknowledgment of black Argentines making their way into the high echelons of society.

Despite white Argentines constant disavowing of the black population,

especially in the artistic arena, black people kept performing milonga and another dance, canyengue—recognized

as the first and earliest version of tango. This early form of tango

retains characteristics of Kongo and Afro-inspired dances. For example,

canyengue is danced in a constant quebrada which means torsion of the hips combined with the sharp bending of the knees. Thus canyengue is danced down

as if extending the couple’s embrace to the earth. The rocking movement

forward and back is also an African-inspired motion. European-inspired,

however, are the cheek-to-cheek and the clinging hook of the woman’s

arm. According to dance-historian Petróleo, “the blacks modified the

posture [in canyengue]—they carried the hand down to the level of the hip(38).”

Petróleo’s statement is important at this point of the essay: African

elements in Argentine’s tradition need not be circumscribed to the

continent of Africa per se, let alone to one country in this vast

territory. They can also be invented and created by the black diaspora

in America. If the purpose of Afro-Argentine studies is to expand the

discursive field of what constitutes “Argentine identity” then one must

broaden the sources of influence and talk about an Afro-foundation on

which the quintessence of modern America is based.

Even

if tango’s black features seem to be hidden under an Italian fedora,

they often resurface underneath the sleeve of a Harlem zoot suit. In

the next section I will discuss the black characteristics in

Argentina’s national dance and music and how they work together with

European traditions in order to become the cultural composite that

tango represents.

IV. Tango’s International Argentine Identity: A Multicultural Approach

It would be ingenuous to try to identify the specific origin of each of

the subtle African elements seen in tango today. It is not my goal in

this paper to attempt such a futile exercise since part of the

greatness of tango is its multicultural and diasporic structure. The

same way that Africans from different nations living in close contact

with each other gradually developed a sort of composite dance—the candombe—that borrowed elements from a number of African dances(39),

later on tango would become an amalgam of a previous amalgam. From

polka to jazz, from habanera to reggaeton, tango’s contemporary

definition requires a tour around the globe. It was not always seen

this way, however, for Argentina’s elite tried vehemently to turn the

country into a European nation in America. In its attempt, tango made a

stop in France where it received a Parisian makeover.

One

steady characteristic that tango has enjoyed since early in the

nineteenth century is the different permutations that make this musical

tradition an all but pure and one-dimensional artistic expression. The

first instance of the term’s usage comes from Montevideo, Uruguay. In

1808 some neighbors in Montevideo asked foreman Francisco Javier Elío

to prohibit the “tangos de negros” (tangos of blacks) among his slaves(40).

Many scholars agree that tango was a generic term that encompassed the

dance, the drums, and the meeting place of black people. Eventually, candombe

became a more specific term that replaced the word tango in the

nineteenth century. Nevertheless, as a concept and as a dance, tango is

derived from classic Ki-Kongo(41) and identified, since its beginnings in South America, as belonging to African descendants in the Rio de la Plata region.

Forward some decades later to the end of the nineteenth century when

the early tango dance, even though popular among inner city men, was

associated with the slum and brothels of Buenos Aires. Perhaps because

of Argentina’s vortex of turning into the “Europe of the Americas,” the

members of the elite class disdained tango during the first decades of

the twentieth century. In 1910 tango began to move from the underbelly

of Buenos Aires to the downtown cafés of the city. Still, during the

second decade of the twentieth century and after tango had reached the

cafés and theaters in London and Paris(42), some white Argentines rejected tango for not being a noble dance. Vicente Rossi, in his seminal work Cosas de negros (A Negro Thing) quotes an Argentine diplomat in Paris who in 1914 exclaimed:

Tango in Buenos Aires is exclusively a dance of the

classes of ill repute and danced in the worst hole-in-the-wall kind of

places. It is never danced in places of good taste nor by distinguished

people. To Argentines’ ears, tango arouses really unpleasant ideas. I

don’t see any difference between the tango danced in elegant academies

in Paris and the one danced in the lower class nightclubs in Buenos

Aires. It is the same dance, with the same gestures and contortions(43).

By saying “gestures” and “contortions” the diplomat avoided

disclosing the truth: that in Argentina there were indeed people of

African descent and thus that tango moved in ways reminiscent of this

heritage. Moreover, the Argentine literary figure, Leopoldo Lugones,

who severely criticized the “brothel choreography” of tango, declared

that “in order for it to be tolerable it is necessary to denaturalize

it…for only a black’s disposition can bear to see this spectacle

without getting repulsed(44).”

Lugones’s words are telling. His statement reveals several issues

concerning blacks’ connection to tango and whites’ need to dissociate

from this. Firstly, we learn from Lugone’s claim that Afro-Argentines

were enjoying tango by attending the cafés and quite possibly dancing,

and secondly, that white Argentines knew that the nature of tango did not reveal a European heritage, therefore the need to fabricate a new and whiter complexion.

During its stay in London and Paris, tango transfixed European

danceophiles and, in turn, they transformed tango into what it is

today. For instance, it was a Parisian who designed the

“tango-dress”—made so that women could increase their leg extension.

Moreover, it was a poor French immigrant who represents the ultimate

essence of tango: Carlos Gardel. In the 1920s, as today, it was widely

recognized that tango’s true character had been transformed into a new

modality acclaimed to be more “soft” and “elegant.” Additionally, the

wide array of movies such as Rex Ingram’s Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse

from 1921 sent tango into international stardom. As African and

Afro-American characteristics in tango fell prey to the rhetoric of

“invisibility,” the European veneer of Argentina’s identity gained

international visibility—in widescreen dimensions to be more precise.

Tango’s expedition around the world allowed the dance to gain more

exposure, which would translate into richer and more varied sources of

influence. Before commencing our tour around the globe and before

disclosing some of these influences, it is necessary to recapitulate

the legacy of African features that survived throughout the many dances

that came before tango. The call-and-response, traditional in Central

African drumming, takes place in tango when the man leads the woman by

tapping her near the shoulder blade and the woman responds with a step.

The sudden stops when the body freezes for microseconds called cortes, and the quebradas or torsion of the body combined with the sharp bending of the knees, have made it into tango from canyengue. The step called gancho

is simple: with a slight kick, forward or back, the man or the woman

penetrates momentarily the other person’s space. The logic and

symbolism behind gancho is very similar to the ombligada or bumbakana found in candombe.

However, instead of invading your partner’s space with your mid

section, with the belly, in tango it is done with the feet. Also, the

eternal swaying forward and back is an Afro-inspired move still present

in tango.

Tango’s beauty does not stop here. As a

veritable cultural product of the African diaspora, one can find in

tango cases of musical syncretism. One example can be found in the

figure of a white tango composer and bandoneoista,

Astor Piazzolla. Piazzolla’s pen did not know how to discriminate; his

scores filled with sophisticated blends of jazz and classical music,

did not respect strict musical categories. He experimented with jazz

spontaneity by embellishing a line, just like in milonga; then he would introduce a strong riff, reminiscent of the descargas

played by salsa groups and heard in New York clubs in the 1970s; and

lastly, Piazzolla would introduce polymusicality in which he would slip

from scored music to free jazz and back to the score again(45).

Even if tango’s validation was obtained ironically not at home but

abroad during the first half of the twentieth century, during the

second half, Argentines like Astor Piazzolla took advantage of the

myriad musical possibilities that tango could incorporate and re-made

it into a more eclectic sound. As a national icon, tango was born in

Argentina yet raised in the musical fabric of the world, but it was

specifically moved by the black beats in the Americas. Today, tango has

also left a mark in other Afro-inspired musical expressions such as in

the Caribbean reggaeton, a phenomenon born from a blend of reggae,

dancehall, and rap. In a perfect example of musical symbiosis, the

Puerto Rican reggaeton group, Calle 13, recorded this year “Tango del

pecado,” a song that features the production of Gustavo Santaolalla

(two times Academy Award winner) and the collaboration of Bajofondo

Tango Club and Pumasuyo, two South American groups. The tango beat

mixes effortlessly with the tongue-in-cheek and kitschy rap lyrics of Calle 13(46).

In short, Sarmiento’s project of turning Argentina into a “Europe in

America” was partially put in motion through tango. However, asking

tango to remain Europeanized would be uncharacteristic and

contradictory of the moving nature of dance. Christophe Apprill

recognized the kinesthetic and cultural possibilities of the identity

of tango in his book Le Tango argentin en France

(Argentine Tango in France): “Dances are journeys from one continent to

another, round-trip journeys, triangular journeys, journeys from white

Europe to black Africa, from the country to the city, journeys from the

working classes to the bourgeoisie, in its essence, the movement of

dance contradicts immobility and in reality it is a permanent flux(47).”

In its permanent state of fluidity, tango has been able to show at

times a European mask, however, underneath it lies a pulsating

“Afro-foundation” that flirtatiously kindles our senses here and there,

forward and back.

Notes:

1 In Tango: The Art History of Love

(New York, NY: Pantheon, 2005), a book that has been seminal for this

paper, Robert Farris Thompson evaluates the African source of this

phrase uttered at the Shimmy Club—located in the basement of the Casa

Suiza—right before stepping out to dance. Thompson associates the

phrase with the lament cry from classic Kongo, “e, e, e, mbadi lo,”

sung during funerals. He draws a parallel between the phrases not only

for its phonetic similarity but also because in both contexts a hand is

placed on the brows over the eyes; in Argentina, the hands are used as

a manner of looking for the drummers and in Kongo as a gesture of

depression (Tango, 139). Return

2 Ibid., 97. Return

3 Alejandro Frigeiro,

“Usos de Africa en un país ‘blanco’: Reivindicando la tradición y la

identidad negra en Buenos Aires,” Accessed March 19th, 2007,

http://www.lpp-uerj.net/olped/documentos/ppcor/0075.pdf. Return

4 Charles Chasteen, “Black Kings, Blackface Carnival, and Nineteenth-Century Origins of Tango,” in Latin American Popular Culture: An Introduction, ed. William H. Beezley and Linda A. Curcio-Nagy (Wilmington, Delaware: A Scholarly Resources Inc., 2000), 56. Return

5 For more information see the documentary: Afroargentinos = Afroargentines, videorecording, directed by Jorge Fortes y Diego Ceballos (2002; New York, NY: Latin American Video Archives). Return

6 Borges, Antología personal, 1961, quoted in Thompson, Tango, 3. Return

7 Narciso Binayán Carmona, “Pasado y permanencia de la negritud,” Todo es historia 162 (1980), 67. Return

8 Scholars of

Afro-Argentine studies more or less agree on the statistics regarding

the black population in Argentina since the 18th century. For this

essay the majority of the data was taken from Donald S. Castro, The Afro-Argentine in Argentine Culture: El negro del acordeón (Lewiston, N.Y.: E. Mellen Press, 2001). Return

9 Alejandro Solomianski, Identidades secretas: La negritud argentina, ed. Beatriz Viterbo (Rosario, Argentina: Estudios Culturales, 2003), 24. Return

10 Total abolition of slavery came in 1853. Return

11 Castro, The Afro-Argentine in Argentine Culture, 145. Return

12 Ibid., 52. Return

13 Binayán Carmona, “Pasado y permanencia,” 66. Return

14 Thompson, Tango, 91. Return

15 Ibid., 65-66. Return

16 Ibid., 92. Return

17 Ibid., 93. Return

18 According to

George Reid Andrews, “The best known payadores were almost all

Afro-Argentines, among them Pancho Luna, Valentín Ferreyra, Pablo

Jerez, Felipe Juárez, Higinio D. Cazón, and Luis García.” However,

Ezeiza stands out as the best of them. Andrews also presents an

interesting fact that illustrates how important Gabino Ezeiza was in

Buenos Aires: “There are only three statues of Afro-Argentines in all

of B.A., a city that boasts some 200 public monuments. Of those three,

one is a memorial to the institution of slavery, another is a statue of

the semimythical Falucho, and the third is a dilapidated bust of Gabino

Ezeiza, its nameplate missing, set in a small playground in the

outlying neighborhood of Mataderos, the Stockyards.” Andrews, The Afro-Argentines of Buenos Aires 1800-1900 (Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1980), 171-173. Return

19 Thompson, Tango, 95. Return

20 During the slave

trade and the period of slavery, Kimbundu and Ki-Kongo cultures were

mixed together. The mixing of these two nations’ cultures over this

period would have allowed for linguistic combinations of this sort.

Another possible source of origin for the word candombe is the combination of two Ki-Kongo words: nkàndu meaning ‘small drum’ and mbé an onomatopoeic expression referring to 'drum beating', which may be the source of the Brazilian candomblé.

Return

21 Frigeiro, “Usos de Africa en un país ‘blanco’,” http://www.lpp-uerj.net/olped/documentos/ppcor/0075.pdf. Return

22 Ibid., 10. Return

23 Information about the choreography of candombe

was taken from Lauro Ayestarán’s “El folklore musical uruguayo”—quoted

in Estanislao Villanueva, “El candombe nació en Africa y se hizo

rioplatense,” Todo es historia 162 (1980), 45—and anonymous, “Figari, Pintor de Negros,” Todo es historia 162 (1980), 41. Return

24 Thompson, Tango, 66. Return

25 Castro, The Afro-Argentine in Argentine Culture, 51. Return

26 Marvin A. Lewis, Afro-Argentine Discourse: Another Dimension of the Black Diaspora (Columbia & London: University of Missouri Press, 1996), 19. Return

27 Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, Conflicto y armonía de las razas en Américas, 2nd ed. (Buenos Aires, 1953), 183 quoted in Andrews, The Afro-Argentines of B.A., 103. Return

28 Ibid., 103. Return

29 The numbers are

staggering and worth noticing. Professor of History at Columbia

University, Nancy Stepan states, “43 percent of the more than three

million immigrants who settled in the country between 1880 and 1930

were Italian.” Stepan, “The Hour of Eugenics”: Race, Gender, and Nation in Latin America (Ithaca & London: Cornell University Press, 1991), 114. Return

30 Thompson, Tango, 121. Return

31 Ibid., 122. Return

32 For a description of the four stages of candombe read: Andrews, The Afro-Argentine of B.A., 163. Return

33 Thompson, Tango, 127-129. Return

34 Consider too that as a Kimbundu word tshia-tshia

means “to make noise

while dancing with rattles on your ankles,” and

quite possibly the origin of the modern word cha-cha-chá. For more

information read: Fernando Ortiz, Glosario de Afronegrismos (Havana, Cuba: Imprenta Siglo XX, 1924), 159-161. Return

35 Ibid., 127-128. Return

36 Juan José Soiza Reilly, “Gente de color,” Caras y caretas (Nov. 25, 1905), quoted in Andrews, The Afro-Argentine of B.A., 165. Return

37 Thompson, Tango, 130. Return

38 Ibid., 155. Return

39 Andrews, The Afro-Argentine of B.A., 162. Return

40 Vicente Rossi, Cosas de negros (Buenos Aires: Taurus, 1926), 146. Return

41 Thompson has associated eight Ki-Kongo words from which tango could be derived. Return

42 It is not clear

how tango arrived at the French capital although there are three

hypothesis discussed in Nelson Bayardo’s Tango: De la mala vida a Gardel (Montevideo: Aguilar, 2002), 139-144. Return

43 Rossi, Cosas de negros, 168-169. (My translation) Return

44 Bayardo, Tango, 139. Return

45 Thompson, Tango, 209-210. Return

46 Calle 13, “Tango del pecado,” http://youtube.com/watch?v=a0lrzbBiluY. Return

47 Christophe Apprill, Le tango argentin en France, (Paris: Anthropos, 1998), 2. (My translation). Return

Bibliography:

Andrews, George R. The Afro-Argentines of Buenos Aires, 1800-1900. Madison, WI: University of

Wisconsin Press, 1980.

Apprill, Christophe. Le tango argentin en France. Paris: Anthropos, 1998.

Bayardo, Nelson. Tango: De la mala vida a Gardel. Montevideo: Aguilar, 2002.

Binayán Carmona, Narciso. “Pasado y permanencia de la negritude.” Todo es historia 162 (1980):

66-72.

Calle 13. “Tango del pecado.” http://youtube.com/watch?v=a0lrzbBiluY.

Castro, Donald S. The Afro-Argentine in Argentine Culture: El negro del acordeón. Lewiston, N.Y.:

E. Mellen Press, 2001.

Chasteen, Charles. “Black Kings, Blackface Carnival, and Nineteenth-Century Origins of Tango.” In

Latin American Popular Culture: An Introduction, ed. William H. Beezley and Linda A. Curcio-

Nagy, 43-59. Wilmington, Delaware: A Scholarly Resources Inc., 2000.

“Figari, Pintor de Negros.”Todo es historia 162 (1980): 40-42.

Frigerio, Alejandro. “Usos de Africa en un país ‘blanco’: Reivindicando la tradición y la identidad

negra en Buenos Aires.” Accessed March 19th, 2007.

http://www.lpp-uerj.net/olped/documentos/ppcor/0075.pdf.

Lewis, Marvin A. Afro-Argentine Discourse: Another Dimension of the Black Diaspora.Columbia:

University of Missouri Press, 1996.

Rodríguez Molas, Ricardo. "La música y la danza de los negros en Buenos Aires de los siglos

XVIII y XIX.” Hoy Es Historia 8, no. 47:15-26.

Rossi, Vicente. Cosas de negros. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Taurus, 2001.

Solomianski, Alejandro. Identidades Secretas: La negritud argentina. Rosario, Argentina: Beatriz

Viterbo, 2003.

Stepan, Nancy. “The Hour of Eugenics”: Race, Gender, and Nation in Latin America.

Ithaca & London: Cornell University Press, 1991.

Thompson, Robert Farris. Tango: The Art History of Love. New York, NY: Pantheon, 2005.

Villanueva, Estanislao. “El candombe nació en Africa y se hizo rioplatense.” Todo

es historia 160 (1980): 44-52.

|